Revised 16 January 2022

Accepted 25 November 2022

Available Online 10 January 2023

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.046

- Keywords

- Urban planning

Architectural heritage

Adaptation

Contextualism

Protection zones

Historic districts

Public space

Historic environment regeneration - Abstract

The continuity of the history, traditions and culture of the city is an important task of modern urban planning. As part of the research, this article considers examples of urban spaces, whose image contains “extraordinary features of the local”, deep cultural meanings: from individual elements of the historical environment (Krasnoyarsk, Russia), through a system of open public spaces (Yeniseysk, Russia; and Seattle, U.S.), to residential areas of the city (Suomenlinna Fortress in Helsinki, Finland). The focus is on complex reconstruction and regeneration programs for these settlements, and on already built objects. Particular attention is paid to the formation of the open public spaces in the protection zones of cultural heritage objects, which directly or indirectly influence their shaping, architecture and decor, functional and object constituents. The issues of regulating the uniqueness of the place are touched upon.

- Copyright

- © 2022 The Authors. Published by Athena International Publishing B.V.

- Open Access

- This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

1. INTRODUCTION

Krasnoyarsk celebrates its 400th anniversary in 2028. In conjunction with the anniversary date, large-scale infrastructure development, building and improvement of public spaces, and reconstruction of cultural heritage sites have long been planned and are already underway. In addition, Krasnoyarsk annually takes an active part in the national project “Housing and Urban Environment”, which involves the implementation of projects to create a comfortable urban environment and the improvement of yard spaces. However, there is certain uncertainty in the meanings of the projected comfort environment. Of particular importance in the environment in the architectural and urban theory is the understanding of the regional cultural identity, its expression in the elements of open public spaces. In this regard, the author reviews the experience of other cities and countries on the continuity of historical and cultural traditions in the landscape and urban planning, as well as the implementation of urban spaces, whose image contains the “extraordinary features of the local”, the deep historical and cultural connotations.

2. SPECIAL TASKS FOR KRASNOYARSK

The continuity of the city’s history and culture is an important task for modern urban planning. Among the special tasks that confirm the relevance of the proposed study for Krasnoyarsk are the following:

2.1. Preservation of the Unique Natural Landscape, Its Planning and Compositional Relationship With the City

Krasnoyarsk enjoys a unique natural landscape, which is traditionally associated with picturesque forest areas, the water abundant Yenisei River with its numerous tributaries, the syenite rocks of the Sayan spurs “Stolby”.

All this has not only defined the historical process and features of the city’s further development, but also has become the basis for its planning structure. Despite this, the issues of creating the ecological green framework of Krasnoyarsk have not been solved yet. The current Krasnoyarsk environment requires a change of approach to the existing regulation of open public spaces towards strengthening environment-stabilizing functions of green spaces, enhancing biodiversity, increasing the area of specially protected areas, which in turn is aimed at ensuring a comfortable living environment for the population.

2.2. Preservation of Valuable Historical and Cultural Sites and Their Integration Into Modern Urban Life

Recently, Krasnoyarsk authorities have started promoting restoration activities as one of the most crucial strategic tasks in matters of upbringing and education, supporting identity and forming a careful attitude towards cultural heritage sites.

There are remarkable projects to renovate cultural heritage sites, such as the Siberian Cossack homestead where the artist Vasily Surikov was born and lived and which was later transformed into a public space in the form of a museum complex with exhibitions in the courtyard. The main focus is on the historical continuity of the adjacent public open space of the street on which the object is located. At some sites the occupation earth is uncovered, i.e., the ground level corresponding to the time of construction of the buildings is restored along with the paving materials.

Manor buildings, being a complex of various premises included in a single urban structure, can be attributed to architectural objects that form a unique type of urban environment of historic centers of Siberian cities. Today manors are used for the potential development of recreational publicly significant areas of cities [1]. Krasnoyarsk is no exception. There are projects for the integrated redevelopment of historic neighborhoods that include several manors, such as the reconstruction of the historical quarter of K. Marksa-Gorkogo-Bograda-Dekabristov Streets. The project proposes a program for the creation of public space in the block with the inclusion of cultural, social and business functions of the open spaces, oriented towards a unified pedestrian environment with a distinctive image (Fig. 1).

In order to preserve the identity of the historical environment of Siberian settlements it is necessary to develop a comprehensive program for the development of zones of influence of the cultural heritage sites and to consider them as integral urbanistic units, reflecting a particular stage of the urban culture development in a particular place.

Territory of the Historical Quarter in Krasnoyarsk, formed by a group of cultural heritage objects in one protected zone (photo by the author).

2.3. Image Interpretation of Historical and Cultural Context in Open Public Spaces

The relevance of this task is due, on the one hand, to the modern trend of “forming a comfortable urban environment”, on the other hand, to the emergence of numerous already built projects, which have similar functional and object content, detached from the cultural and historical context of the environment and urban morphology. There is a need to rethink approaches to open public space design to foster a sense of “place specificity” in residents. An image interpretation of historical and cultural identity will allow the landscape to be “read” as a text.

3. CONTEXTUALISM OF URBAN ENVIRONMENT: GLOBAL EXPERIENCE

The geography of the examples discussed below is based on the research objectives, theoretical knowledge, the author’s own design experience and the information obtained during a field survey of each site considered in the article. The key point in selecting urban spaces for the study was the historical and cultural context embedded in the concept of urban environment.

The city and the culture are inseparable concepts, moreover, they are so interrelated that they form an integral object of knowledge [2]. Urban space reproduces deep cultural meanings, reveals the value-normative system of a given culture. The new appeal to a local one-of-a-kind tradition – the neo-vernacular one1 – was characteristic of the development of architecture in the 1960s, according to which the project clearly conveyed a sense of place in the use of certain materials, cultural traditions and stylistic preferences. “Local character” was not a direct reproduction or an exact copy, but in “quasi” or in “the same vein” form. Neo-vernacular became a possible compromise, conceived as a combination of traditional and modern [3]. Another approach to the “extraordinary particularity of the local” is taken to have originated at Cornell University in the early 1960s in the philosophy and movement of “contextualism”. It emerged in the process of research into the mechanism of formation of binary models in urban planning, providing its comprehensibility [4]. E. Boyarski, having studied the works of K. Sitte, distinguished the most important binary pair, the opposition of mass and emptiness or figure and background, which is the key to the contextual approach to the urban space. According to it, there were explained the necessity of understanding urban context, accentuating not the objects but the fabric between them, projecting from the outside inwards, reading the deep meaning through the obvious things. The modern reading of the historical and cultural context in the urban environment can be seen in related trends in the development of landscape planning: “Cultural Context” and “Spirit of the Place”, which had a significant influence on the development of style trends in architecture [4,5].

An exemplary case is the city of Seattle, U.S., which follows the concept of cultural heritage preservation by integrating into contemporary society life through regeneration and reconstruction programs.

One such program is being actively pursued in landscape and urban planning, following the “Green System” concept proposed by landscape architect John Charles Olmsted in 1903: “I know of no other place where nature itself encourages to create parks... It is the green system that can become one of the city’s main attractions that have made it famous throughout the world”.2 This concept is based on the principles of Frederick Law Olmsted. In 1908, the city’s green system plan was revised following the expansion of the Seattle area by adding three districts (Southeast, West and Ballard), so the length of the “scenic boulevards” linking the parks into one system increased to 50 miles (just over 80 km). To this day, Seattle’s green system is recognized in the U.S. as the best example of a systematic approach to the design of open public spaces. The city follows these principles in its designs, which help maintain a balance between the natural and man-made components of the environment, ensuring environmental sustainability. In addition, to preserve the “Olmsted legacy”, there is a complementary program run jointly by the Seattle Parks and Recreation (SPR) and Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks (FSOP), a not-for-profit organization, aimed, among other things, at multiplying the existing park lands stock and designing new landscaped recreational spaces according to Olmsted’s philosophy of open spaces for everyone [6]. That is why Americans themselves call Seattle the “Queen of the Evergreen State”, because there are 3 Open Green Spaces per inhabitant and 94% of the housing units are within a 10-minute walk of a park3.

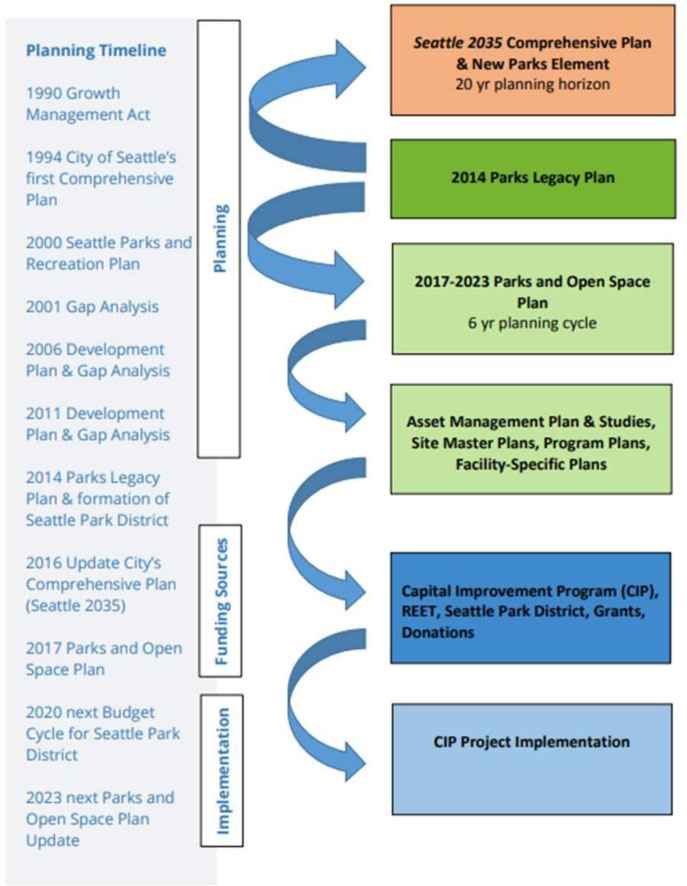

The green system strategy is enshrined in several interlinked documents concerning urban planning at different levels. For example, the 2017 Parks and Open Space Plan4: a 6-year plan approved by the City Council that describes SPR facilities and lands, addresses Seattle’s changing demographics, and sets out a strategic vision for how community needs will be met in the future. The plan works in conjunction with other planning documents, including Seattle 2035: the City of Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan 5, the 2014 Parks Legacy Plan 6, the 2016 Seattle Recreation Demand Study7, the 2016 Community Center Strategic Plan8 and other city plans (Fig. 2).

Block diagram of the 2017 Parks and Open Space Plan. Source: [7].

Harmonization of the urban landscape places great emphasis on the creation of a recognizable “visual code” within it, which carries not just information about the spatial and functional dimension of an area, but whole phrases, images that allow one to read and unravel the environment and identify themselves with the history and cultural context of a given place.

The development of the surrounding area over time requires a landscape adaptation of the outer shell of historical sites to the new conditions of their functioning, whether this applies to residential development or parkland. The methods of incorporating the history of the city in the contemporary environment, applied to the objects of landscape architecture, help to elaborate more deeply on the continuity of traditions and strengthen the historically narrative role of the urban space.

Another cultural heritage regeneration program operating in Seattle is First Settlers Preservation. Since 1970, eight historic districts have been formed in Seattle. The appearance and historic integrity of the buildings and public spaces in each district are regulated by a Citizens Council and/or Landmarks Preservation Board according to processes and criteria established by city ordinance [8].

One such area that has been called the “historic heart” of Seattle is the 35.61 hectare Pioneer Square neighborhood, where the first settlers came in 1852. During the Klondike gold rush (1896–1902), it was from here that fortune hunters headed for Alaska. After a fire in 1889, the Pioneer Square neighborhood was completely rebuilt. The area is characterized by late-19th-century brick-and-stone buildings and one of the best surviving collections of Romanesque Renaissance urban architecture in the country. Due to problems with the drainage system, the new quarter was built on a higher level, literally burying the remains of the historic Pioneer Square. Many buildings were built with two entrances, one on the lower level and one on the upper level. Pioneer Square became a bustling area with taverns, entertainment venues and obscene hotels. This atmosphere prevailed until the mid-20th century.

In the 1960s, the Pioneer Square Quarter underwent a redevelopment during which some of the historic buildings, while retaining their outer facades, were reconstructed into multi-level car garages. By the 1970s, there had been a direct threat to the city as a cultural ecosystem. This accentuated the awareness of the importance of the cultural history in the project area very important. Large sums of money were allocated to preserve and restore the historically significant area. In the early 1970s, Pioneer Square was added to the National Register of Historic Places (city preservation district).

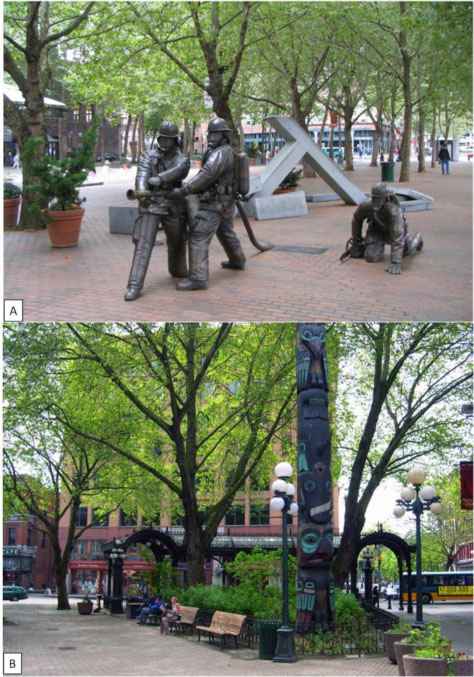

A – Monument to firefighters saving the city from fire (Pioneer Square, Seattle); B – Native American totem, erected in Pioneer Square, in front of an iron open gazebo built as a canopy over an underground latrine in 1909; Preserved in its original form it is known as “the finest underground comfort station in the United States” (photos by the author).

Today the area is a concentration of art galleries, Internet companies, cafes, sports bars, nightclubs, bookstores, the social and cultural life of the city. Pioneer Square is part of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, other parts of which are located in Skagway and Alaska. A special Underground Seattle tour with preserved streets, entrances and storefronts of houses underground is also a special sightseeing facility for tourists.

The spatial dialogue between the city and its historical heritage is manifested by historical allusions in the examples of object design. Symbolic content and the use of signs allow the modern landscape to be read as a text, introducing visitors to the history not only of the city, but also of the whole country (Fig. 3). The city itself is interested in preserving historical uniqueness. Each of Seattle’s historic districts has specific regulations, mainly aimed at saving the unity of street facades and the environmental design of public spaces (regulating building facades in terms of style, architectural details, color, construction and cladding materials, including the organization of windows, shop windows, entrances, number of stories, engineering, landscaping materials: paving, curbs, surface runoff features, types of landscaping, lighting, etc.)9. In addition, new construction in transitional areas bordering historic districts is also regulated, as the development of buffers must be visually compatible and not be detractive and overwhelming in relation to historic properties. For example, the “Design Guidelines for New Construction on the North Lot in Pioneer Square” [8], contains requirements for the functional use of the area and the interior of buildings; the physical parameters of development, architectural details of buildings, utilities design elements, canopies, lighting, roof forms and materials, applied mechanical elements; the organization of parking areas; comprehensive landscape gardening of streets and pavements; permission for public art.

Historically valuable city’s areas create a specific artistic image, characteristic of one of the stages of its development. The continuity of cultural traditions enables not only to preserve the historical and cultural layer in the city’s fabric, but also to create a comfortable, highly aesthetic, individualized environment for human life, which gives an impulse to the humanization of the urban space.

There are similar examples in the Krasnoyarsk Krai. For the 400th anniversary of Yeniseysk in 2017, a research work on the regeneration of the central part of the city was prepared, which included the development of a “Passport of Requirements” [9] for the urban environment. The requirements for pavement types, small architectural forms, lighting, facades, color schemes, types of landscaping and assortment, as well as the functional destination of certain areas of the historical part of the city were analyzed in detail. Moreover, the architectural and spatial design of all open public spaces made by one team of designers deserves special attention, as this work contributes to the uniformity of solutions to emphasize the uniqueness of the historic environment (Fig. 4).

Visualization of the design concepts for the regeneration of the central part of the city of Yeniseysk in the Krasnoyarsk region. Source: https://proektdevelopment.ru/projects/yeniseysk.

A unique example of incorporating a cultural and historical monument into modern city life is Suomenlinna, a bastion system of fortifications on islands near the Finnish capital of Helsinki. From the 18th to the middle of the 20th century, fortifications protected Helsingfors from the sea, and the role of the fortress in the defense against three different countries, Sweden, Russia, and Finland, made it particularly important. Since the 1960s, the fortress has been a museum in the open air and in 1991 it was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List as a monument to European military architecture of its time. The garrison houses the Naval Academy of the Finnish Navy [10]. Suomenlinna Fortress is not only one of the most popular sights in Finland, but also one of the districts of Helsinki with about 800 permanent residents. Administration of Suomenlinna fortress is an independent department of the government (Suomenlinna Board of Administration)10, acting under the Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland, which is responsible for restoration works, maintenance, development and coordination of tourism activities in the fortress. The fortress and garrison buildings have been restored and converted into flats, offices, banqueting and conference rooms, restaurants and museums, as well as socially significant facilities.

For example, there are a kindergarten and a library in the fortress wall of the bastion fortification in the center of Iso Mustasaari (Fig. 5). The foundation stone was laid by King Gustav III of Sweden on 8 June 177511. During restoration work, a copper casket containing the king’s coronation medal, two other medals and two coins was discovered in the foundation. The Toy Museum is located in a wooden building constructed in 1911 during the Russian regime (Fig. 6). The building is the former summerhouse of Russian Captain Vasilyev, who served at that time at the fortress headquarters in Vyborg. The dacha was built with a gable roof design, original for that time12.

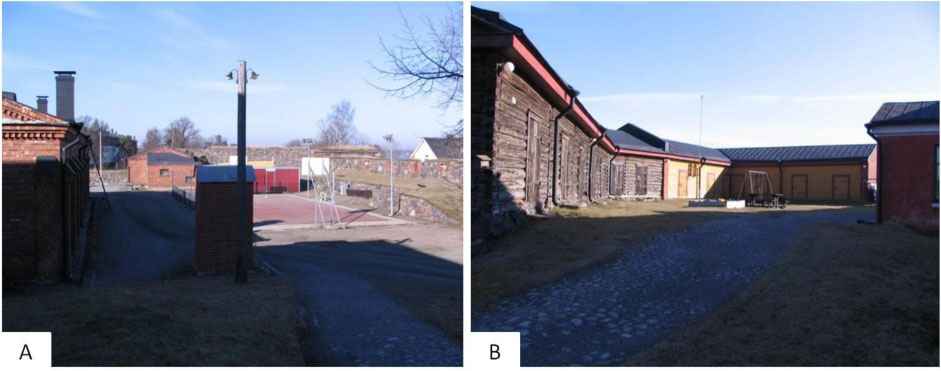

There is also an open prison on the territory of the fortress, where around 100 people are permanently incarcerated, where focus is more on rehabilitating rather than punishing and reintegration back into society (Fig. 7). Prison inmates wear normal clothes and move freely around the island with an electronic controller (GPS sensor), and undergoing labor therapy they are engaged in repairing fortifications and gardening, maintaining the uniqueness of the fortress. The involvement of a person in collective work and recreation, attraction to information and cultural sources – libraries, museums, theaters, etc., in general, to the cultural environment – this is the program for the social rehabilitation of prisoners to overcome feelings of inferiority.

Suomenlinna fortress wall of the bastion fortification, in which there are living quarters, a kindergarten and a library. A – view of the wall from the main tourist routes; B – view of the wall from the side of the residential buildings (photos by the author).

The Toy Museum: dacha of Russian Captain Vasilyev; Suomenlinna Fortress, Helsinki, 1911 (photo by the author).

Open-type prison in Suomenlinna. A – Volleyball court; B - service and bedroom blocks (photos by the author).

Clearly the environment is shaped by anthropogenic, abiotic and biotic factors, based on the cultural context of the Place [11]. The environment of a city is created by society, and it is in the environment that a personal worldview, moral norms, behavior and aesthetic principles are formed. “A person is ... a bearer of cultural heritage and, at the same time, an initiator of communicative-cultural relations” [12].

4. CONCLUSION

This article displayed an analysis of urban spaces, whose image contains extraordinary features of the local, deep cultural meanings: from individual elements of the historical environment (Krasnoyarsk, Russia), through a system of open public spaces (Yeniseysk, Russia; and Seattle, U.S.), to residential areas of the city (Suomenlinna Fortress in Helsinki, Finland), and this can bring the following conclusions:

City development programs that contain plans for shaping the urban environment should be targeted (geolocated), address specific site problems and meet the needs of a particular consumer, broadcast the local context.

Local town-planning standards should take into account spatial differentiation of the city, specificity of building density, population number, parameters of functional zones depending on administrative districts as well as remoteness of natural areas and water objects in order to really form a comfortable environment.

Project activities today should aim for historical continuity of the place, architectural and urban integrity of the environment with architectural surroundings and natural landmarks, reflect the regionalism, contain an educational component.

In order to preserve the identity of the historical environment of Siberian settlements, it is necessary to elaborate a comprehensive program for the development of territories – zones of influence of the cultural heritage sites – and to consider them as integral urban planning units, reflecting a particular stage of development in the urban planning culture in a particular place.

The tasks of preservation of the identity of the landscape and green areas of the city should be put on a par with the issues of protection of the cultural heritage, including their ecological efficiency. The image of the national space as a place where people live is always perceived through the forms of the landscape.

Contextualization of the urban environment must be paired with symbolic references, use of signs of cultural history, which would provide for “their reading” and thus become part of the creation process of the urban landscape. The historical, cultural and natural potential of the area, which connects the past and the present through environmental design, serves as the basic material.

Footnotes

Neo-vernacular is exceptionally uncommon.

Sources: Seattle Post Intelligencer 21 September 1902; Ibid. 1 May 1903; Ibid. 4 October 1903; Ibid. 18 October 1903; Ibid. 2 April 2003; Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks website (https://www.seattle.gov/friendsofolmstedparks); Seattle Dept. of Parks and Recreation website (https://www.seattle.gov/parks); HistoryLink.org Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History: David B. Williams, Parks of Seattle: The Olmsted Legacy https://www.historylink.org/ (Accessed: 15 May 2001) – Note: This file was updated by Walt Crowley on 18 April 2003.

The 2017 Parks and Open Space Plan is a public hearing and discussion document, reviewed by the Board of Park Commissioners, approved by the Superintendent, the City Council’s Parks Committee, and ratified by the City Council. Under this, the Washington State Office of Recreation and Conservation supports the city in obtaining state grants to help implement outdoor recreation projects and open space acquisitions [6].

Approved for 20 years and formalizes the land use of the areas.

A comprehensive analysis of the park system and individual locations, helping to outline development goals and strategies.

Contains results of sociological research on consumer demand.

The document analyses the development of 27 community centers, which are seen as organizations whose activities are linked to, among other things, the development of Seattle’s parks and recreational areas as foundation for the healthy environment.

Independent government department (Governing Body of Suomenlinna).

Kirkkopuisto | Kyrkparken | Church Park — [Suomenlinna Sea Fortress] — Information inscription (Finnish | Swedish | English) on the sign in front of the cultural heritage site.

The Toy Museum — [Suomenlinna Sea Fortress] — Information inscription (English) on the sign in front of the cultural heritage site.

REFERENCES

Cite This Article

TY - CONF AU - Natalia Unagaeva PY - 2023 DA - 2023/01/10 TI - Contextualism: A Modern Interpretation of the Historical and Cultural Context in an Urban Environment BT - Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2022) PB - Athena Publishing SP - 337 EP - 345 SN - 2949-8937 UR - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.046 DO - https://doi.org/10.55060/s.atssh.221230.046 ID - Unagaeva2023 ER -